Language and Culture: Two Families’ Stories

Angela Branz-Spall, Helena, MT, currently serves as the Montana Director of Migrant Education at the Office of Public Instruction. Angela’s professional life of 50 years has been dedicated to providing educational equity for disadvantaged children through program administration, curriculum design and teaching.

Angela has served as the Director of the Bilingual and Civil Rights Programs, as well as the Migrant Education program. She has worked with the indigenous languages in Montana on language restoration issues and knows some of the last speakers of certain tribal languages. Angela wrote the first Civil Rights grant for the state that ensured that they would have funds to assist the development of native language orthographies and is active in the Human Rights Network nationally. “I love my work even in these dark days and know that it is my heritage that has inspired me these many years to stay at it.”

Angela’s mother, Santina Branz, emigrated from Roncone, Trentino to Wallace, Idaho in 1936 at age 13 with her mother Serafina Mussi Franzoi and siblings to join her father, Celso Franzoi who had emigrated earlier. She passed away on October 3, 2018.

Please see more about Santina and her husband Luigi Modesto Branz of Sanzeno, Val di Non, proprietors of Louie’s Gem Store and Bar in Burke Canyon, Idaho, in the story following Angela’s.

ANGELA’S STORY

Because I believe in the preservation of language as a central part of any culture, I offer some details which attempt to indirectly address how most indigenous languages like Nonese (Crow, Cheyenne, etc.,) survive, even though the dominant culture tries to eliminate them. These dialects are often looked down upon by the dominant culture and thought of as irrelevant artifacts.

While I understand both of my parent’s dialects, I do not speak either very well because I do not have their lived experiences and because my mother insisted on my learning Italian as a result of her schooling during Mussolini’s rule in Italy.

Both mom and dad’s dialects preserve the color and imaginations of the feudal peasant populations who used them and who have passed them down orally to their progeny to preserve their cultures and histories much in the same manner that the languages of American indigenous tribes have preserved their cultural memories of what occurred before the great genocides in North America through the maintenance and restoration of their languages.

Mom’s dialect is a bit French sounding as her area was once part of Alsace-Lorraine long ago. Nonese my father’s dialect, is the language spoken in Val di Non for centuries and is thought to derive from Ladin.

Even prior to WWI, all my family spoke their dialects and Italian if they had the privilege of at least some education. They did not speak German and so are considered ethnic Italians. They loved the language of Verdi and Puccini in Italian opera and celebrated the poems of Dante Alighieri.

Serafina and Celso Franzoi

During WWI, my maternal grandmother, Serafina Mussi, while a teenager, did learn some German because she, along with others in the village of Roncone, were forced to assist the Austrians with the building of the fortresses along the front lines of WWI. She carried sacks of materials for making cement on her back up the steep alpine mountains which she would tell me about when I was a child.

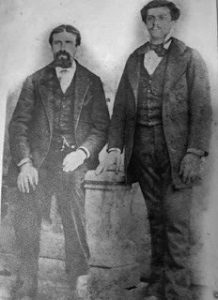

Antonio Mussi (left) and his brother

Her father, Antonio Mussi, was also part of the collateral damage of the war, having been killed by an Austrian landmine while pasturing his cow. Her brother, Felice, was paralyzed when an Austrian soldier hit him on the head as the soldiers were departing at the close of the war.

Maria Pizzini

Her mother, Maria Pizzini Mussi, died of a heart attack as a result of hearing that news. That left my mother’s mother, Serafina, her sister Pina, her brother Bartolomeo, and paralyzed brother Felice, orphans.

While my mother could, of course, speak the Roncones dialect from her hometown Roncone in Val di Guidicarie, now called Sella Guidicarie, she was educated to speak and write in Italian. She had a more rigorous education in her village with most of the teachers coming to Roncone from Milan post WWI.

Luigi Branz (with hat), his parents, his sisters, one of his three brothers

I grew up in a home where my dad, Luigi Branz (born in 1913) from Sanzeno, Val di Non, primarily spoke Nonese with other immigrants from Val di Non who lived in our area in Idaho. While he did go to school in Sanzeno, WWI caused great disruption to his family.

Because his father, Zeffiro Branz, had been in New York City, Hazelton, PA and Rock Springs, WY at various times prior to the war, he was suspected by Austrians to be an American sympathizer and to have avoided the Austrian draft. He, along with 1500 other Trentini, was sent to a concentration camp at Katzenau, Austria where he was confined during the war. He underwent starvation, torture, and grave illness while there, and once the war was over, he was a changed man. (See the book, “Dynamic of Destruction – Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War” by Alan Kramer for more about the camps.) As a result, it was necessary for my father to help his mother during those dark and difficult years.

My father delivered telegrams from immigrants of the Val di Non who were in America to locations throughout the valley to help support his family. It was from those telegrams that his American Dream began.

By 1927 he made his way to America and began his life in a new world, working first digging tunnels for the New York City subway system, later in Hazelton, PA, he stayed with his Aunt Maria (ne Albertini) Marchetti and did odd jobs there, then on to the brick factory in Milwaukee, the mines of Butte, and finally working at the Haywire lease operated by his uncle Angelo Albertini (his mother Filomena’s brother) in Gem, Idaho.

Dad would converse in Nonese with his Val di Non relatives in Shoshone County, Wallace, Idaho. Those included his uncle Arcangelo (Angelo/Albert) Albertini his Aunt Josephine Albertini Voltolini (sister of his mother) his Rossi cousins, and Angelo’s son Johnny Albertini who was fluent in both Italian and Nonese.

There were fewer immigrants in Shoshone County from Val di Guidicarie, but my mom would speak to the Rizzonelli’s, the Armani’s, the Bazzoli’s and her own family the Franzoi’s in her dialect. In time, there were no more speakers of her dialect in Shoshone County, Idaho and very few of my father’s as well. So, the only times they were able to speak their very first languages – the first languages their mother’s spoke to them – was when we traveled to Italy and with each other and the few remaining immigrants.

I took my mom to the Trentini nel Mondo Convention held in Denver in the late 80’s so that she could be reunited with her best childhood friend from Roncone, Gilda Bazzoli, who had immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1932, two years before my mom left Roncone. Mom missed Gilda terribly after the Bazzoli family left Roncone and hoped to see her one day in America. When mom came to America in 1934, her family settled in the West, so she and Gilda communicated by letter for the following fifty some years.

When she and Gilda saw each other in Denver it was as if no time had passed and they were once again, inseparable for a time, speaking in the dialect and reminiscing about their childhoods.

After my father passed away in 1997, we took mom by train to Canonsburg, PA so that she could once again be reunited with her best friend Gilda. We spent two weeks with Gilda and her family singing the old songs like “La Montanara” and eating polenta and crauti, capucci and other dishes typical of Roncone.

Mom and Dad mainly spoke to each other in dialect and learned each other’s quite well. They also spoke, read, and wrote in English with my mother being more proficient because she went to school in Idaho and in Washington while my father did not.

SANTINA’S STORY

Santina Pia Branz was born in the Dolomite Alps of the Trentino Alto Adige Region of northern Italy in a small village called Roncone on January 14, 1921. She was the first child of Celso Franzoi and Serafina Mussi Franzoi.

The area of northern Italy where Santina was born was part of the front during WWI and had been a part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire prior to that time. The war left areas along the front devastated and Santina’s family was no exception. Her grandmother Maria Pizzini Mussi and her grandfather Antonio Mussi both were civilian casualties of the war and her mother’s brother, Felice was permanently disabled by a land mine.

Serafina with children – Maria, Santina, Renato

Like many men of that time and place, Santina’s father, who was a blacksmith, and her uncle Battista migrated to the USA to work in the coal mines of Pennsylvania and later went west to Rock Springs, Wyoming and eventually to Wallace, Idaho where they worked at the Sunshine Mine. Santina, her mother, brother and sister stayed behind in the village of Roncone, waiting for the day that they would one day be able to join their father and uncle in America.

During her childhood Santina was stricken by the German measles epidemic which took the lives of many children and due to complications was bedridden for a year and, at one point, near death. It was during her illness that she developed a life-long devotion to Saint Luigi of Gonzaga, a nobleman who gave up his riches to serve the poor. Santina not only survived her illness, she lived to the advanced age of 98 1/2 without ever having any major illnesses, hospitalizations or surgeries, all of which she attributed to St. Luigi.

At the age of 13, Santina and her family were finally able to make the voyage across the ocean on the SS Rex to New York City, and then, across the United States by train to Missoula, Montana.

The family of four had little money and ran out mid-way on their journey. Mom used to love to tell people that through the generosity of the conductor of the train, they were invited to the dining car and treated to dinner and new foods like bananas and Jell-O which they had never seen. She always spoke about the kindness she and her family were shown on that journey west and encouraged us to treat others in the same manner.

They were reunited with their father and uncle in Missoula and made the exciting trip across the mountain to the town of Wallace where their father had purchased a little home on River Street. The children enrolled into Our Lady of Lourdes Academy and made many new friends. Having completed 8 years of schooling in Italy, mom advanced quickly and began to learn English and the customs of her new country.

One year later, the family moved to Greenacres, Washington where their father purchased a small farm on which they raised fruits and vegetables. Mom enrolled in Central Valley High School and with her love of languages, art, history and music, excelled in her studies.

It was there that her talent for singing was recognized and that her dream of being an opera star began. She began to study voice under the direction of Lyle Moore at Gonzaga University where once again she encountered her patron saint of old, St. Luigi of Gonzaga and where she promised herself that if she were ever blessed with children, she would make sure that they would attend school there. She won several vocal competitions, including a Metropolitan Opera tryout competition.

Santina and Luigi’s wedding

In 1938, while visiting friends from her hometown in Italy, who lived in Wallace, Idaho, she was introduced to Luigi Modesto Branz, also of the same region, and again it seemed that her patron saint Luigi was looking out for her. They were married in 1939 at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Greenacres and the wedding party was said to have gone on for a week!

Santina and Luigi in front of their store/bar

They were proprietors of Louie’s Gem Store and Bar and had three children all of whom went on to attend Gonzaga University providing Santina with yet another of her answered prayers.

Santina and Angela in front of their store

Santina, John and Roger (her sons)

Santina was a life-long member of St. Alphonsus Parish in Wallace, Idaho, where she participated in Catholic Daughters of America and the St. Alphonsus women’s choir. She sang at the wedding of Senator Mike Mansfield’s son in Burke, Idaho and was the featured singer for many a midnight mass at St. Alphonsus Church.

She was a needlework expert, a superb gardener, and an amazing cook and homemaker. Above all, she was a devoted wife, mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, aunt and friend. Mom never had a cellphone or a computer and never learned to drive a car. She did not make it to the stage at the Metropolitan Opera House. But every day of her life, she was devoted to her family and committed to her faith and she touched each person she met with her incredible kindness and authenticity.

She spent the last six years of her life in Helena, Montana near her daughter, Angela Branz-Spall, and passed away on October 3, 2018.

Santina Branz

A Tribute by Dan Zadra

October 14, 2019

My name is Dan Zadra. I think I am a distant cousin of Santina, and here’s why:

My grandfather Fred Zadra emigrated to America from the little Northern Italian village of Revo, which is just a couple valleys away from Santina’s village of Roncone. Like Pina’s husband Louis, my grandfather worked in the silver mines in Wallace, Idaho, and my father Augie was born in Black Bear, just down the road from Louie and Santina’s home and store in the Burke Canyon.

Now, If your family roots are in the Dolomite mountains of Northern Italy, then you are a Trentini like Santina. And if your forefathers and foremothers emigrated to the Silver Valley, you have the right to call each other cousins. The Branz’s, the Fellins, the Zadras, the Cantamassas, the Voltolinis, the Carons, the Albertinis and other Italian families in the Silver Valley — we may not always get along perfectly, but we are all cousins in spirit or in fact, and we are all part of the great Italian emigrant experience, including the migration of the early 1900’s to the Silver Valley.

And this morning, as we celebrate Santina’s life, we should reflect on the fact that Santina and her husband Louis represent some of the best qualities and proudest traditions of our Trentini ancestors — those hard-working dreamers and doers who came to America seeking a better life.

“Coming to America to start a new life has always been hard,” wrote historian J. Ollie Edmunds, and he might have been writing about a young girl named Santina who fell in love with a hard-working miner named Louis in 1938. Together Louis and Santina set up shop — a little grocery store and saloon—right by the side of the road in one of the roughest mining districts in the American West and set out to make a life and raise a family together.

“This country was not built by those who relied on somebody else to take care of them,” said Edmunds. “It was built by men and women who relied on themselves…who dared to leave the old country to shape their own lives in a new world…who had enough courage to blaze trails on the frontier or in rugged mining camps or timber towns across the American West…and with enough confidence in themselves to take the necessary risks. This self-reliance is our American legacy…a precious ingredient in our national character, one which we must thank our immigrant family members for — thank you, Santina! — and one which we must pass on to our children and grandchildren.”

As I look out on your faces today, I am jealous and happy for those of you who got to share a whole lifetime with Santina. What stories you must have (I know because I have sat with Angela for hours and listened to her talk endlessly with love and devotion about her Mom and Dad). As for me, I only knew Santina for 10 years or so, but I treasure every day I had with her.

For the next few minutes I would like to share a couple of my favorite Santina memories with you, in hopes that they bring a smile to your face, and some comfort to your heart on this difficult day of loss.

I will never forget the night I met Santina. She was in her late eighties and still living independently in the same house in the Burke canyon where she and Louis had raised their kids and ran their bar and store since 1938. That night I joined the Albertinis in Wallace for Huckleberry festival. We all decided to have a steak for old time’s sake at Albi’s Gem Bar, and we invited Santina to join us, which she did. My son Gus and I were lucky enough to sit next to Santina at dinner that night, and we immediately fell in love with her as, with the aid of a couple glasses of vino, she told delightful stories of her life in the Silver Valley back in the thirties, forties and fifties.

When dinner was finished, Santina needed a ride home, so I volunteered and she accepted. Little did she know that my car was a racy little jet-black Mini Cooper convertible. When we walked her out to the car I thought she might take one look and go back inside. Instead, she smiled that big beautiful smile and said, “Well, okay then, let’s go.”

It was a beautiful summer night, about 70 degrees in the Valley, and with the top down and my son stuffed in the tiny backseat, and Santina riding shotgun, off we went into the night. As we roared up the Burke Canyon, I pushed the accelerator to the floor at one point and caught a sideways glance in the moonlight of Santina gripping the safety bar for dear life. Her gray hair and neck scarf were streaming wildly in the wind like a World War I fighter pilot, and I could see her big bright eyes and that beautiful smile. She was like a 90-year-old little girl that night.

When we got to her house, it was late, and I’m sure most 90-year-old ladies would have wanted to say a quick good night and grab some sleep. But not Santina. She knew, from our dinner conversation, that my son and I were hungry for more stories about our Trentini ancestors and life in the valley, so she invited us in….For the next hour and a half she showed us around the house, and the wine cellar, and her Italian garden, and of course she opened up the saloon and store and regaled us with story after story of serving the miners and their families in the old days . She talked about how Louie had courted her, how he sang to her, what a good hardworking thrifty man he was…and how he convinced her to marry him by first owning a car, and second by promising her new furniture for their house. It was a night my son and I will never forget.

Another Santina memory: Two or three years ago, I bought an old Idaho Roadhouse called the Hilltop Bar & Grill. I’m writing a book about the history of the Hilltop. It’s going to be called “If These Walls Could Talk,” and it will include interviews with people who have come there to dance or drink or carouse over the last 95 years or so.

The Hilltop was built in 1927 and Santina came to the Valley in 1938. As you all know Santina had a great memory, so one day when she was well into her nineties, I asked her if she remembered ever going to a little roadhouse in Kingston called the Hilltop. She thought and thought, and then her eyes lit up. Sure enough she remembered that the Hilltop was a dance hall— called a “honky tonk” in the those days. And she said that she had gone there a few times. She looked at me with her bright eyes and said, “I was pretty then, and the miners all wanted to dance with me.” And then, of course, Louie became her man, and she says she never went back to the Hilltop.

That day, I took a picture of Santina and I plan to make it the first picture in the book, so that everyone can see that she was not only pretty in her twenties, she was absolutely radiant and beautiful her entire life. There is an old saying that says “After age 50 we get the face we deserve.” Well, I think you will all agree that a lifetime of caring and joy and compassion and good humor showed through in every aspect of Santina’s beautiful face until the very last day of her life.

One last memory: About a year ago, a young Italian videographer named Vincenzo Mancusco wrote to me from Italy. He is creating a full-length documentary about the Trentini immigrants who came to America and worked in the mines in places like Pennsylvania, Colorado, Washington and the Silver Valley. He asked me if I would arrange interviews with Italian families here in the Silver Valley, which I did, and some of you here today took part in those interviews.

Santina was in failing health at the time Vincenzo made his visit to Wallace, but I called Angela and said, “Wouldn’t it be amazing if your Mom’s story could be included in this documentary of the Trentini emigration experience.” A couple days’ later Angela came back with the good news that Santina was excited about participating. So I drove Vincenzo to Angela’s home in Helena Montana where he interviewed both Angela and Santina for most of the day. I don’t know where she found the energy, but Santina was radiant that day, beautifully dressed, full of life and grateful to be able to talk about coming to America, raising her family and pursuing her dreams.

On the way home to Wallace, Vincenzo turned to me and said that Angela’s and Santina’s memories were priceless for his documentary. And he had a nickname for Santina that is especially fitting for our memorial today. He said that, as she recalled memories of the old country and of her life with Louis and her children in the Burke Canyon, that her face and eyes lit up with joy. Occhi d’angelo he called her: Occhi d’angelo means “Angel eyes.”

I later found out from Angela that one of Louie’s pet names for Santina was Angel eyes.

Let me close today with one last thought about Santina Branz. The thought is this:

“The world knows nothing of its greatest heroes.”

Santina may have spent a simple life in a small house in a hardscrabble mining camp, but Santina was a hero to me — and probably to most of you in this room too.

To me, Santina’s life is proof that some of the best and most important people in our world are never featured on the 6 o’clock news…or see their name up in lights…or get to ride in open cars in the big parades. But those things were never important to Santina Branz.

Santina was never about fame or acclaim, she was always about family and tradition.

She wasn’t about money or titles, she was about spirit and heart…about caring and compassion.

The only titles Santina really cared about were these: Loving daughter…loyal hard-working wife…caring friend…thoughtful cousin and auntie…big-hearted mother and grandmother and, of course, a proud Trentini. These everyday roles comprised Santina’s chosen path in life — and if you think about it, she was world-class at every single one of them.

As I said earlier, the world knows nothing of its greatest heroes. Like Santina, most of us never get a shot at life’s grand awards — no Oscar, Emmy, or Nobel Prize. But, as Santina’s life reminds us, we all have a shot at one worthwhile pursuit — the chance to touch the lives of everyone we meet with joy, love, compassion and caring along the way. And, hopefully like Santina, we will get to the end of life, knowing that we left the world a better place than we found it.

One of my most prized possessions is a big red antique neon BEER sign that hung like a beacon for the miners for years outside the Branz family saloon and store. I found that sign in a Wallace antique shop, bought it, restored it, and hung it in my own saloon at the Hilltop. And when I turn it on every day, I think of Louis and Santina and Angela and all their family members.

You know, I think today’s world could use a lot more Santina in it.

If the world had more Santina in it, there would be lots more family dinners and traditions.

If the world had more Santina in it, people would grow old, but they would never BE old. Instead of saying no to a surprise midnight ride in a little black sports car, people would jump right in the front seat at age 88 and say, “Well, okay then, let’s go.”

If the world had more Santina in it, people wouldn’t just honor their fathers and mothers, they would honor their husbands and wives, and brothers and sisters, and nieces and nephews, and children and grandchildren, and neighbors and friends.

Cara Santina, we say “A Presto” and “Good-bye to you, hero.” at least for now—and, oh, how you will be missed. We will always love you…always remember you…never forget you.